According to President Truman, What Justified the Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki?

Can nuclear state of war exist morally justified?

(Image credit:

Getty Images

)

Was the decision to bomb Hiroshima and Nagasaki morally wrong? 75 years afterward, the question is more than difficult to answer than offset appears.

I

In the early 1980s, the Harvard constabulary professor Roger Fisher proposed a new, gruesome style that nations might bargain with the determination to launch nuclear attacks. Information technology involved a butcher's knife and the president of the The states.

Writing in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, Fisher suggested that instead of a briefcase containing the nuclear launch codes, the means to launch a bomb should instead be carried in a capsule embedded nearly the middle of a volunteer. That person would behave a heavy blade with them everywhere the president went. Earlier authorising a missile launch, the commander-in-chief would first accept to personally kill that one person, gouging out their heart to remember the codes.

When Fisher fabricated this proposal to friends at the Pentagon, they were aghast, arguing out that this human activity would misconstrue the president's judgement. But to Fisher, that was the point. Before killing thousands, the leader must outset "look at someone and realise what death is – what an innocent death is. Claret on the White House rug".

Killing a person with a butcher's knife may be a morally repugnant act, all the same in the realm of geopolitics, by leaders accept justified their diminutive acts as a political or armed services necessity. Following the nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki – 75 years ago this month – the decision was justified only in terms of its outcome, not its morality. The bombing ended Globe War Two, preventing further deaths from a protracted disharmonize, and arguably discouraged the descent into nuclear war for the residuum of the 20th Century.

This article contains details some people may find upsetting

Y'all might besides similar:

- Deep ideals: The long-term quest to decide right from wrong

- How would nuclear state of war change humanity?

- Hiroshima and Nagasaki: Women survivors of the atomic bombs

Yet those positive consequences cannot obscure the fact that on 6 and ix Baronial 1945, two of humanity's nearly destructive objects brought the horrifying power of the cantlet onto two civilian cities. We tin attempt to describe the events through numbers: at least 200,000 people killed by the flashes, firestorms and radiation; tens of thousands more injured; an unquantifiable inter-generational legacy of radiation, cancer and trauma. We tin can remember the individual stories – of mothers and children, of priests and doctors, of ordinary lives transformed in a moment. Or nosotros tin memorialise the relics left behind, as described in the verse form No More Hiroshimas: "The ones that made me weep... The bits of burnt vesture. The stopped watches. The torn shirts. The twisted buttons".

But there is possibly no adequate manner to capture that scale of human suffering.

Can it always be right to launch a nuclear attack against civilians? In what circumstances could such a determination be morally justified? In recent years, researchers and philosophers have explored the moral questions raised by nuclear weapons, and their conclusions suggest at that place are few piece of cake answers.

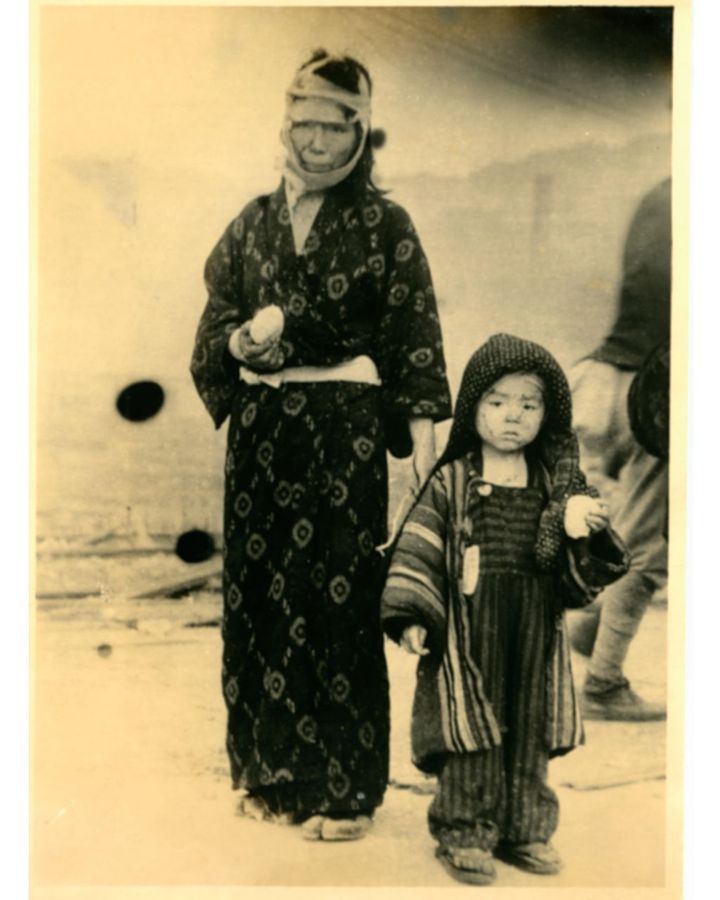

The survivors are known every bit "hibakusha" (Credit: Alamy)

The greater skillful

Start, let's consider the argument that the US authorities, led by president Harry Southward Truman, made for the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombing. Post-obit the events, the United states of america framed its determination as an unfortunate just necessary human activity for the greater good. "The master political, social, and military machine objective of the U.s.a. in the summer of 1945 was the prompt and complete surrender of Japan," wrote the US Secretarial assistant of State of war Henry Stimson in 1947. The culling – a ground invasion – could accept resulted in the death of more than ane one thousand thousand U.s. soldiers, Stimson asserted, and potentially many more than on the Japanese side. Perhaps that explains why in 1945, a Gallup poll found that 85% of Americans approved of the bombing.

If Truman felt any regret, he did not show information technology. One of the closest hints of contrition came from the diary of the secretary of commerce, who wrote that Truman chosen a halt to whatsoever further bombing after Nagasaki because "he didn't like the idea of killing 'all those kids'".

A wounded child in Hiroshima (Credit: Alamy)

Nevertheless, while in that location is no doubt that protracted state of war betwixt the allies and Japan would take led to a heavy expiry cost, some historical accounts suggest that reality was more circuitous at the time. Past focusing retrospectively only on the outcome – the end of the fighting and 75 years of nuclear-free warfare – alternative historical paths were closed off. What would the Japanese have washed if the Americans had elected a show of forcefulness first, dropping a bomb in Tokyo Bay rather than onto two cities? Had the Emperor already resolved to ask his authorities to give up? And was the approximate of one million American deaths through a ground invasion authentic? These what-ifs will never be known.

The reasoning that Stimson presented for the determination can nonetheless be seen as a commonsensical statement that the bombing prevented a greater degree of overall suffering, says the Japanese philosopher Masahiro Morioka. In a recent paper, he drew parallels between the Hiroshima/Nagasaki bombings and the utilitarian dilemmas raised by the "trolley trouble". Originally proposed by philosopher Phillipa Foot, one of the simplest versions of this thought experiment asks people to weigh up whether they would sacrifice one person's life to salvage v, by redirecting the rails of a runaway trolley to impale that individual.

In his university lectures in Japan, Morioka presented this version of the trolley trouble to his students, and like many people who are asked to consider the scenario, they told him they would divert the trolley and then that only one person dies. "They were shocked to realise that they made the same determination as Truman and Stimson," he says.

President Harry Truman (left) is briefed on the bombing past secretary of war Henry Stimson (Credit: Getty Images)

Yet Morioka argues that seeing Hiroshima and Nagasaki through the sanitised logic of a utilitarian greater good argument obscures the perspective of the dead and injured. "How the victims would think is erased from the trouble," he explains. "I believe that we should imagine seriously how the killed victims would call up if they were alive here."

Morioka told me that while he tin encounter the basic logic in the justification of the bombing, he believes that it lacks humanity. "By making a justification, we are led to pretend that the perspective of the victims did not be at all, which is morally and spiritually wrong, problematic and repugnant."

Degrees of separation

Perhaps that's also what Fisher had in mind when he proposed his butcher'southward knife idea. Blood on the White House carpet. The neuroscientist Rebecca Saxe tackles the moral dilemmas underpinning Fisher's protocol in a class she teaches on the science of morality at Massachusetts Institute of Applied science (I attended information technology concluding year equally office of MIT's Knight Scientific discipline Journalism fellowship).

Like Morioka, Saxe points out that if the U.s.a. president was fully committed to the commonsensical logic of reducing the total amount of suffering during state of war, they should accept no qualms with carving out the person'southward heart to go the nuclear codes. What is ane extra innocent life, if you are prepared to kill tens of thousands for the greater good?

An injured 21-year-onetime soldier who was exposed to the bombing with subcutaneous haemorrhage spots on his body (Credit: Gonichi Kimura/Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum/Reuters)

Perhaps some presidents would reach for the knife, but as Fisher'south friends in the Pentagon pointed out, the horrific proximity of the act might give them intermission. After all, killing a person to get the codes has all the elements that make a savage murder prohibited and punishable. As Saxe points out, the deed would exist premeditated, intentional, not in self-defence, and instrumental (it uses people as a means to an end). If you agree that murder by this definition is always wrong for individuals, tin there be a moral justification for leaders and nations?

Psychologists who written report our moral attitudes have described the squeamishness felt past the idea of murder upwards close equally "activeness aversion". When people are asked to identify themselves in a scenario that involves pushing, stabbing or shooting, for instance, they are less likely to support the thought of killing for the greater expert.

In the trolley problem, a majority of people support the case for switching a lever to divert the tracks, allowing the trolley to kill 1 person. But many hesitate when presented with a different scenario that involves pushing a man from a bridge to block the lethal trolley. (It is a grim coincidence that this unfortunate person is sometimes described equally a "fatty human being", which was as well the lawmaking name of the flop dropped on Nagasaki).

The mathematics of expiry in this scenario are the same – one life for 5 – only something about the deed of pushing feels incorrect to many people. (Though notably not all – one study showed that college students with psychopathic traits, for example, are more likely to endorse utilitarian judgements that involve harm).

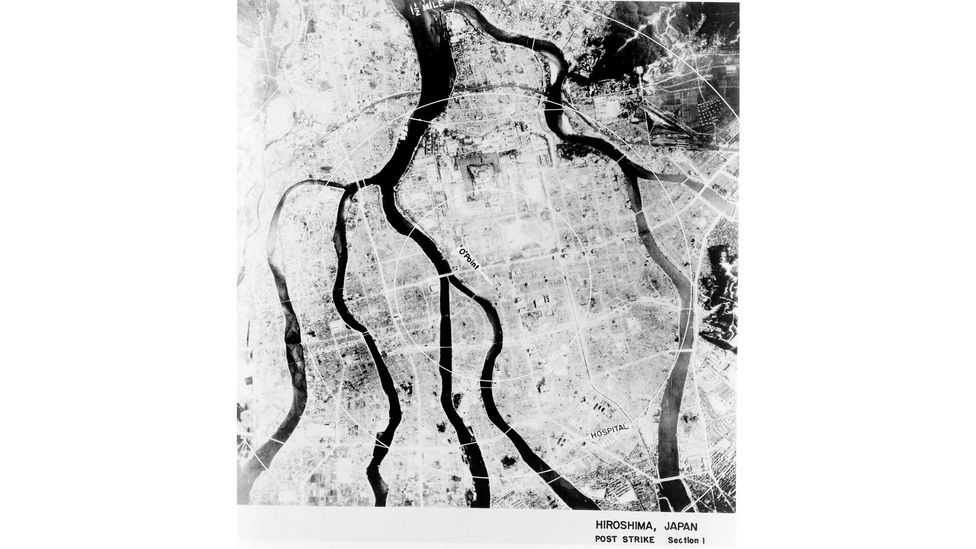

Hiroshima and its people from the perspective of a Us military plane (Credit: Library of Congress)

In 2012, one grouping of psychologists designed an experiment that captured people's "action aversion" in a truly inventive way. The researchers asked participants to perform acts of violence such as striking an experimenter's imitation leg with a hammer, or whacking a realistic toy baby onto a table. Even though people knew they would cause no harm, the acts prompted a strong psychological response, suggesting we may take a hard-wired moral aversion to doling out direct violence.

As the psychologists pointed out, at that place is a "dark side" to such action aversion. Their findings too suggested that when people are discrete from the realities of harm, in that location are fewer mental obstacles that might otherwise requite them pause. "Signing one'due south name to a torture order or pressing the push button that releases a bomb each have existent, known consequences for other people, merely equally actions they lack salient backdrop reliably associated with victim distress," they wrote.

Perhaps a geographical and temporal disengagement from the human realities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 goes some of the way to explaining why so many Americans notwithstanding support Truman'due south decision. Perhaps Stimson'south example for a greater good – all those hypothetical American lives saved – too still carries weight in the national memory. V years ago, on the 70th anniversary of the bombings, the Pew Research Centre asked Americans again what they thought of the bombing. While a lower pct approved compared with the 1940s, 56% of US respondents said they believed the conclusion was justified.

The perspective of the Japanese is, unsurprisingly, utterly unlike. In the Pew survey, only fifteen% of Japanese people agreed that the bombing was justified. And while 40% of Japanese people described the events as "unavoidable" in a 2016 report conducted by the broadcaster NHK, a higher proportion of 49% said "they can't forgive even now". This is despite the fact that an e'er-smaller proportion of Japanese people nevertheless survive from 1945: the average historic period of the hibakusha – the victims who directly experienced the bombing – is now well over fourscore years old.

Other nations, too, would seem to approve less of nuclear attacks than the Us, at least if snapshot surveys are anything to go by. In one poll, people around the world were asked if "nuclear weapons are morally wrong". People in the US were notably less probable to concur compared with citizens of the Britain and France, which are too nuclear powers.

Few houses and buildings were left standing near footing zero in Hiroshima (Credit: Mitsugi Kishida/Teppei Kishida/Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum/Reuters)

To dive deeper into The states attitudes to nuclear weapons, one 2013 report titled "Diminutive Aversion: Experimental Bear witness on Taboos, Traditions, and the Non-Use of Nuclear Weapons" asked Americans to put themselves in the position of a leader authorising a strike on a base of operations in the Middle East. The researchers wondered whether there might exist a moral "taboo" against using the nuclear choice, compared with a conventional weapon. They found that the people in their study were actually more likely to make a determination based on the effectiveness of the weapon and whether or not it would atomic number 82 to escalation, rather than shunning nuclear weapons as inherently incorrect or taboo.

Yet Brian Rathbun of the Academy of Southern California argues that there is more nuance to the morality of the decision-making displayed in this study than get-go appears. "There was a presumption that those people were morally dastardly," he says, but that conclusion is based on simply one very narrow definition of morality.

Psychologists and neuroscientists one time studied moral decision-making predominantly through the lens of harm, fairness and concern for other people. For case, i approach was to peer at people's brains while they caused or observed pain in others. But around a decade ago, it began to emerge that people's "moral foundations" – how they decide what is right and wrong – are more complex, and crucially, differ according to background, civilization and political ideology.

Progressive liberals, for instance, are more than likely to make judgements based on the moral foundations of "care" and "fairness", aiming to avoid harm to others, or embracing political issues such as equality (which might suggest that scientists previously had spent a bit as well much time focused on studying only liberal morality). Traditional conservatives, by contrast, are oftentimes more probable to prioritise the moral values of "loyalty", "respect for authority" and "purity/sanctity", and and then make moral choices that favour traditions, societal stability, and preserving the style of life of their communities and nations.

It's not that conservatives are uncaring and liberals disloyal – the moral foundations can be nowadays across gild – but the betoken is that each person has different priorities most which values are nigh important to them when weighing upward what is right or incorrect. "We consult these underlying moral intuitions to figure out our position on an issue that nosotros've never heard," says Rathbun.

Consider people'south reasoning for justifying violence. When a conservative supports policies like the capital punishment, torture or military force, they are non setting aside their ethical values, even if a liberal might strongly disagree. And a liberal supporting a protest motion that leads to public disorder and violent clashes with authorisation might find disagreement with their political opponents, but they are guided by what they believe is moral.

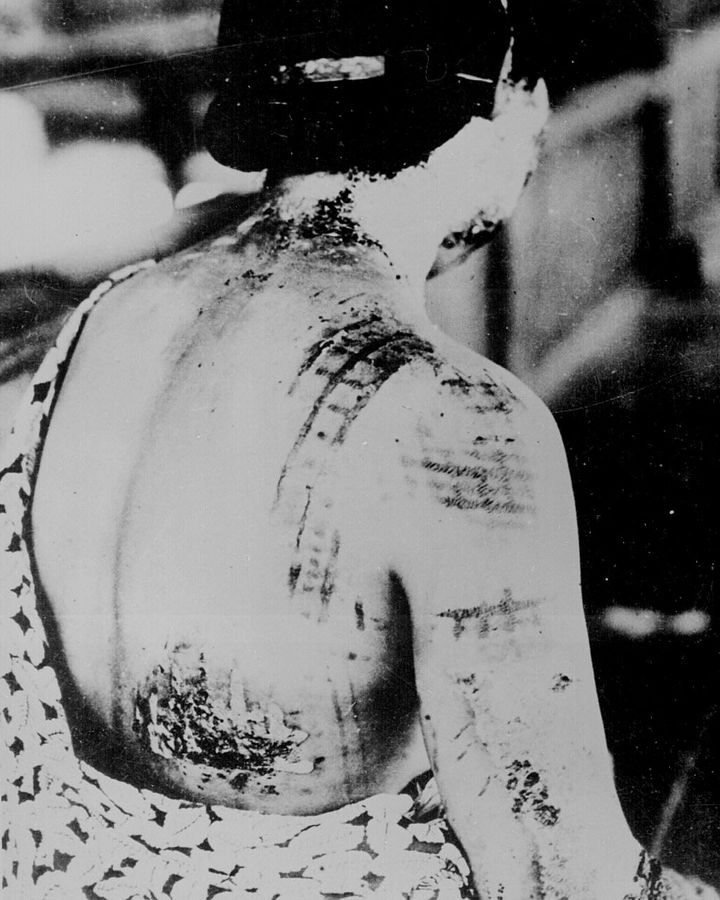

At least 200,000 were killed and many tens of thousands of people were injured with burns and worse (Credit: PD)

Last twelvemonth, Rathbun and Rachel Stein of George Washington Academy ready out to explore how people'south moral foundations affected their attitudes to nuclear weapons. Like with the "Diminutive Aversion" study, the pair asked participants from the The states to put themselves in the shoes of a leader weighing up whether to make a nuclear strike confronting a armed services base of operations, varying factors such as weapon effectiveness, the identity of the enemy, and associated casualties.

The pair found that people who prioritised so-called "binding" moral values of loyalty and respect for authority – which probably evolved to strengthen the "in-grouping" and protect against external threats – were more likely to approve of the utilize of nuclear weapons in their scenarios. They also, peradventure unsurprisingly, were more than likely to endorse the deportment of a leader who had launched a nuclear attack. Even stronger support for nuclear weapons was institute amid people who value the moral rule of "an center for center" – perhaps i of the oldest ethical principles.

People with these bounden and retributive values were also less likely to abandon their position as noncombatant casualties rose. Yet, they were not indifferent – support for the nuclear option dropped fairly steeply one time the casualties exceeded 10,000, and was very depression in all groups past the time the expiry price reached a million.

All this suggests that it's incommunicable to answer whether the utilise of nuclear weapons is inherently correct or wrong – whether they should be taboo or allowed nether some circumstances – because information technology depends on the moral framework of the private.

For those who would wish to avoid nuclear state of war, an arguably more important question to ask would be how the aggregate moral views of a nation collectively influence a pol'south choices in the fog of conflict. What matters, says Rathbun, is that public opinion has the ability to influence the likelihood of a nuclear launch. "Politicians rely on an intuitive sense about what they think the public will let," he says. "They're always operating under a sense of 'what can I practice' and 'what tin I non do'."

And equally historical trends in polling have shown, public attitudes towards nuclear weapons can shift over fourth dimension. While support in the US is overall lower than the mid-20th Century, in that location's nothing to say that this can't reverse. One recent report, for instance, found that public backing for the ban on The states nuclear tests has declined since 2012. Meanwhile, the current United states administration is reportedly contemplating a resumption of testing on American soil.

A hereafter leader, with their finger hovering over the nuclear button, will always make their decision under what Rathbun calls a "shadow of morality".

"The conclusion that's been reached since fourth dimension immemorial is that international relations is a realm of homo interaction devoid of moral content," he says. "From an evolutionary point of view, I remember that's impossible. Human being beings but cannot aid simply moralise."

Mark the anniversary of the bombings in nowadays-day Nihon (Credit: Getty Images)

The end of everything

At that place is one concluding moral dimension to consider when exploring the rights and wrongs of nuclear weapons, which was articulated past the Oxford University philosopher Toby Ord in his recent book The Precipice. The explosive power of thermonuclear bombs is so keen in the 21st Century that they pose an existential risk of triggering a nuclear wintertime, caused past smoke from firestorms blocking sunlight for years. "Hundreds of millions of direct deaths from the explosions would be followed by billions of deaths from starvation, and – potentially – by the finish of humanity itself," he writes.

Ord argues that human extinction would be a disaster of such magnitude that working to forbid information technology should be the world'southward number one moral business concern. Not only because everybody on Earth would perish, but also considering it would hateful that trillions and trillions of as-still unborn people would not alive – and flourish – in the coming millennia.

"Nosotros stand up poised on the brink of a hereafter that could exist astonishingly vast, and astonishingly valuable," Ord writes. Even so our power to destroy ourselves – and all the generations that could follow – is outpacing our wisdom. In Ord'southward view, the morality of nuclear war looks quite dissimilar if yous consider it as an existential, species-level threat, rather than through the lens of national conflicts.

Subsequently WWII, a monument was built at ground zero in Hiroshima. It features the words: "Let all the souls hither rest in peace; for we shall not repeat the evil."

"The give-and-take 'nosotros' means not merely the people in Hiroshima urban center, but also all human beings on Earth, including the unabridged Japanese and US citizenry," according to Morioka, who shows the monument to his Japanese students whenever he discusses the 1945 bombings with them.

Five years ago at this site, a former U.s. president paid his respects to the Japanese people, and said the following words: "The very spark that marks united states every bit a species – our thoughts, our imagination, our language, our tool-making, our ability to set up ourselves autonomously from nature and bend it to our volition – those very things also give united states the capacity for unmatched destruction… Technological progress without an equivalent progress in man institutions tin can doom us. The scientific revolution that led to the splitting of the atom requires a moral revolution as well."

It doesn't affair which president said the words. What matters was that, similar 10 other U.s. presidents of varying political affiliations since 1945, he did not find himself facing the same decisions that led to that terrible calendar week 75 years ago this month. For all this fourth dimension, both Republicans and Democrats – along with the leaders of other nuclear-armed nations around the world – have had the opportunity and ability to reach for the codes that launched an atomic bomb against their enemies. Roger Fisher'southward controversial proposal to embed those protocols in the heart of an innocent volunteer was, patently, never taken up. Yet remarkably, mayhap luckily, no global leader since Truman has ever used them. Whatever your views on the rights and wrongs of atomic weaponry, that cannot exist anything but a victory.

* Richard Fisher a senior announcer for BBC Hereafter.

--

Join one one thousand thousand Future fans by liking us on Facebook , or follow us on Twitter or Instagram .

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter , called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future , Civilisation , Worklife , and Travel , delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Source: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200804-can-nuclear-war-ever-be-morally-justified

0 Response to "According to President Truman, What Justified the Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki?"

Post a Comment